We, human beings, are fundamentally narrative creatures. We all need a story to live, our brains are wired to make sense of our world and ourselves through stories. Friedrich Nietzsche said, “He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how”. Stories attempt to answer our why questions.

Earliest cave paintings and the latest Pixar movie are a testament to our enduring fascination with stories. We will continue to be captivated by them even through the times of AI.

Why narrative matters

Jordan Peterson says, “It is the near-simultaneous discovery by literary critics, researchers into robotics and artificial intelligence, cognitive scientists and neuropsychologists alike that we do and even must perceive reality through a story. Or more accurately, they discovered that a story is a portrayal of the structure through which we perceive reality.”

Our world is too complex to navigate without direction and purpose. To help us make sense of our reality, we create narratives that help filter and focus on what matters.

The real-life stories that inspire us, the fictional stories that stretch our imagination, business stories that motivate us, and ideological stories that unite or divide us evolve into overarching meta-narratives we inhabit, whether we are aware of it or not. Surprisingly, we are often drawn to the ones that help us cope with our struggles and the wounds we carry. They attempt to provide answers to our deeper human need for identity, belonging, significance, purpose, and transcendence.

For example, “The American Dream” is a popular cultural meta-narrative in which the story of prosperity and success is attainable through hard work, grit, and determination. “Rags to Riches” is another story archetype of a journey from poverty or obscurity to a position of great wealth, success, or fame. Many such meta-narratives exist. They could be of a political, cultural, ethnic, historical, or religious nature.

It is essential to recognise that we all inhabit such meta-narratives, and they hold utmost importance personally. Whatever doesn’t fit one’s narrative often fails to register as meaningful or important.

When a business wants to be successful, the narratives its customers inhabit, shaped by the challenges they face, the emotions they experience, and the aspirations they strive for, must be at the heart of the company’s story.

Understanding story design

Steve Jobs, the great business storyteller, said, “The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values and agenda of an entire generation that is to come.”

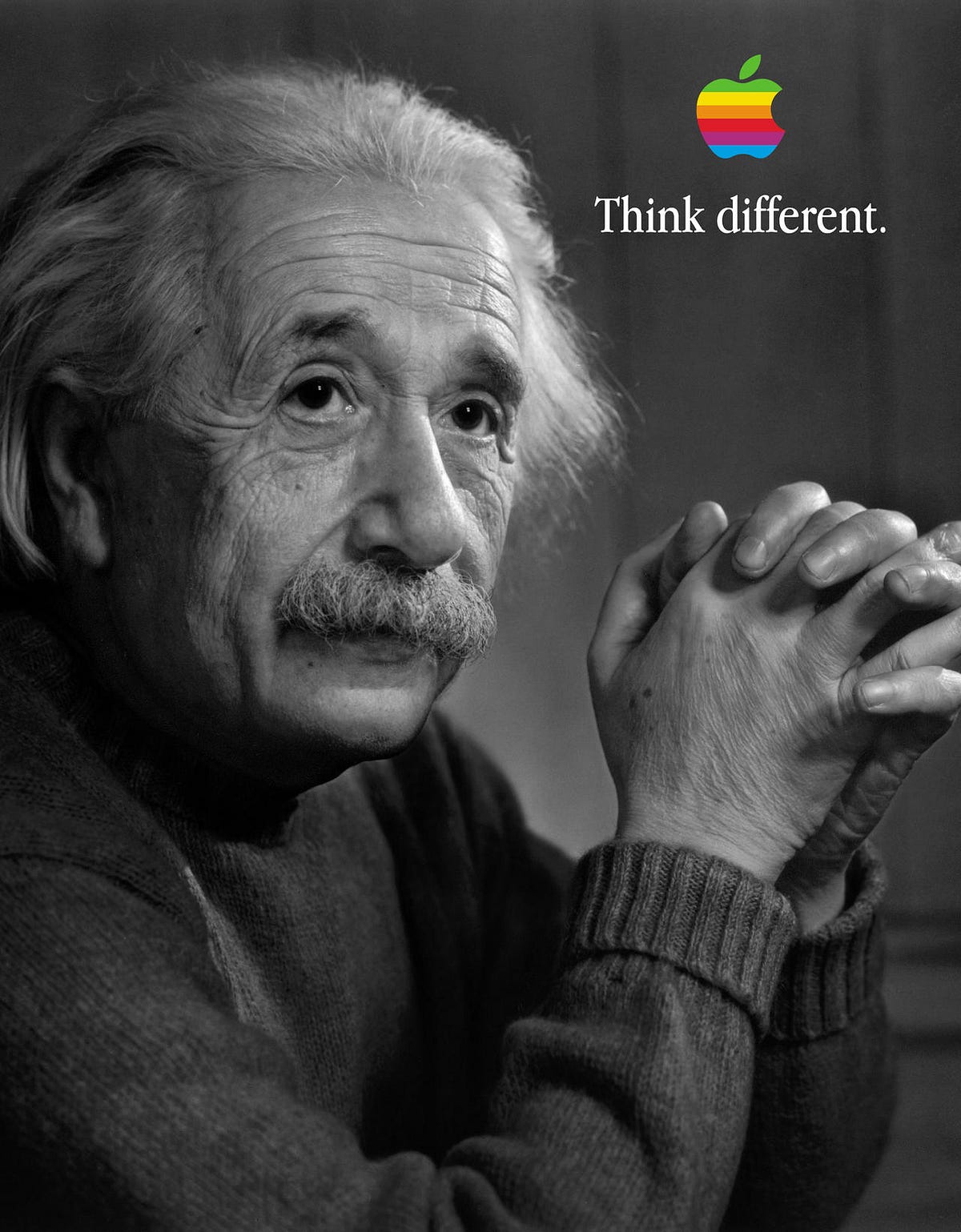

However, in 1983, when he launched Lisa, he released a nine-page ad in the New York Times, explaining all its technical features, which nobody outside of NASA was interested in. The computer failed. But after he left Apple, his experience at Pixar or Nike’s ‘Just do it’ campaign may have convinced him of the power of story. That’s why when he returned, his understanding of the business changed. He focused on the emotions, frustrations, and aspirations of their customers who felt they were the crazy ones, misfits and rebels. Then he said to them, “Think different”

Earlier, Apple’s story was all about itself. Its new story is its customer’s story. “(1) It identified what their customers wanted (to be seen and heard), (2) idefined their customers’ challenges (that people did not recognise their hidden genius), and (3) offered their customers a tool they could use to express themselves emotionally (computers and smartphones).”

While facilitating Kintsugi Story workshops at Mountain Retreat, I am slowly coming to learn how different circumstances draw us to particular narratives. They could be our existential needs, psychological wounds, childhood formation, past experiences, social status, and so on.

In a story, what the character wants and aspires to become is often perceived as a cure for the fears/trauma the character encountered in the past.

In fiction writing, they call it a character’s ghost; it is something in your character’s past that haunts him in the present. Every person carries their past wounds and struggles. Our perception of our world is shaped by the wounds and fears that our past experiences have created. These may not always be very traumatic incidents; they could be small feelings of neglect, inability or instability, etc., during childhood. Fortunately for some, those wounds heal, leaving scars nevertheless.

Apple’s core audience for its personal computer was artists, designers, and students, who often felt like outsiders in the technology space. They felt people did not recognise their hidden genius; they felt neglected. Apple echoed their emotions and praised their perceived identity as the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels. The Think Different narrative resonated with these people because Apple cared about their frustrations and told a transformative story.

I want to call Steve Jobs a great business story-thinker, not just a storyteller, because he designed his business around his customers’ narrative. He created products and services that showed a better future. This created a lasting impact on his customers because he empathised with their emotional needs and the fears they carried.

It is debatable whether Apple’s products truly created a positive impact on our generation. That is a different topic for another day. Nevertheless, the influence was deeper. Story thinking is a powerful skill to either positively transform people or manipulate them. People in power always use it for the latter goal.

Most people are often ignorant of the narratives we inhabit. But, when someone articulates the story they’re living, it creates a moment of recognition — ‘Yes, that’s exactly how I feel.’ Rene Girard said, “Man is the creature who does not know what to desire, and he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires.”

Our desires and our narratives are mediated through others, especially our models. Models are those who we are captivated by, those with lofty aims, and we wish, if we are brave, we could be possessed by their spirit. We not only desire the things that they desire, but we also desire to become like them. “All desire is a desire for being.” ― Rene Girard.

If businesses need to make sense to their customers, they need to articulate their story through their models. When people buy Apple products, they are buying into Steve Jobs’ narrative that misfits, creatives, and rebels can become geniuses just like him.

Apple doesn’t sell computers; they sell “think different”. It’s a narrative about creativity, rebellion against conformity, and belonging to an elite tribe of geniuses.

Nike doesn’t sell shoes; they sell “the athlete in you”. It’s a ‘hero’s journey’ narrative about overcoming obstacles and achieving one’s potential.

However, narratives are not just the stories we tell our customers. First, it is the customer’s story we tell ourselves, and then let it inform us in creating products that meet their needs.

Donald Miller says, “What most brands miss, however, is that there are three levels of problems a customer encounters. In stories, heroes encounter external, internal and philosophical problems. Why? Because these are the same three-level problems human beings face in their everyday lives.” To put it simply, an external problem, which is often tangible, causes our customers to experience an internal frustration, which is philosophically wrong!

In an era of abundance, great products don’t just solve surface-level problems — they help us become who we want to be. The more brands address the deeper needs for identity, belonging, significance, purpose and transcendence, the more they connect with customers and the broader industry and culture. Mere utility-centred products can be quickly replaced.

Does it make sense only for multi-billion-dollar companies? No, even a mom-and-pop shop that is empathetic to customers’ needs, fears, and aspirations can become successful.

Moreover, narrative design is not just for the MVP stage; it is a continuous effort, as narratives must evolve in tandem with cultures.

Designing narrative products

To build the right narrative for our customers, we need to strengthen our right-hemisphere thinking in our organisations. Unfortunately, most product design and development is dominated by left-hemisphere thinking.

McGilchrist, in his book ‘The master and his emissary’, argues that the two hemispheres don’t divide tasks by type (logical vs. creative), but rather by how they attend to the world. The left hemisphere offers narrow, focused attention — it grasps things in isolation, categorises, and manipulates. It sees the world as static, knowable, and mechanical. We end up building what we can measure, not what matters. However, the right hemisphere provides broad, sustained attention — it perceives context, relationships, and the whole. It remains open to what is new, ambiguous, and alive.

He uses the bird foraging for food while watching out for predators as a central analogy for the two hemispheres’ different and often competing modes of attention.

Narratives are fundamentally right-hemisphere phenomena. You can’t understand a story by dissecting it into data points or features. Narrative dead products may work efficiently, but they lack significance on a deeper level. A more efficient product could easily replace them.

For example, here is what a pure left-hemisphere restaurant (let’s call it OptimalBite) owner may say, “Our Q3 data shows table turnover averaging 47 minutes. Competitors are at 42. We’re losing 10.6% revenue per seat per day.” Whereas a dominant right-hemisphere owner (let’s call it Nonna’s Kitchen) may say, “Our customers — they’re exhausted. Overworked. Disconnected. They’re hungry for belonging. I want them to feel that they have come to their grandmother’s kitchen in Tuscany. To feel they are home. They belong.”

But when you ask customers from the former restaurant? “It’s fine. It’s convenient. The food is… okay.” What will the customers from the latter restaurant say? “We’ve been coming here for five years. The chef remembered my husband died last year and gave us a special toast in his memory.”

Right-hemisphere thinking involves seeing the whole before the parts, which means capturing context, emotions, and behaviour — that is, understanding products within the customer’s life narrative. This involves asking questions like, How do products fit into the actual lived context of people’s lives? What are the larger cultural/meta narratives at play? What fears and frustrations do they carry?

Understand which archetypal narrative resonates with your customers. For example, the ‘hero’s journey’, the ‘mastery story’, etc. Which narrative rings true emotionally? What kind of person does this product encourage users to become?

Ask how your product intersects with customers’ lives. Grasp what the product means metaphorically and philosophically, understanding human connections and their identity formation and see products as part of a journey, not isolated moments or features.

Right-hemisphere thinking prioritises synthesis over analysis. It fosters ecosystem thinking, allowing for ambiguity and narrative evolution, and remains open to new and unexpected possibilities.

Story-first businesses begin by studying their customers, the stories they are living, capturing their emotions, frustrations and aspirations. Field trips, contextual enquiries, day-in-the-life immersions, story workshops, model mapping, story pattern mapping, among others.

Airbnb started as a great story-first company; it was revolutionary. However, today it has drifted to standardisation, efficiency, and algorithms. Now it is like any other hospitality business.

The key is that right-hemisphere practices don’t replace left-hemisphere rigour — they inform it. Both are necessary. But the right must lead.

The ethics of narrative design

Narrative design is also a powerful tool for manipulation because it exploits some of the fundamental human emotions and needs.

In any good story, the protagonist begins believing a lie — a flawed narrative in Act 1 — but is very convinced. However, at the midpoint of Act 2, a crisis point in the story, the protagonist has been struggling under the burden of his lie. At this moment, he finally sees the Truth. When he chooses to accept it (which will cost him a lot, even his life), transformation begins. It leads to a new, wholesome narrative with renewed aspirations.

Good stories are about people facing challenges that test them. Transformation is the evidence that the test mattered — that going through the fire either forged something stronger or revealed what was already there. Without transformation, we’re left wondering: what was the point of this story?

People are drawn to narratives that take them from a state of lack to a more complete and fulfilled one, as they perceive it, inspired by their models. Apple iPhone customers may discover that they have become more creative or better storytellers, just like their model Steve Jobs himself.

Most of the compelling narratives promise transformation. It’s often what separates a good story from a manipulative one. Or a good product from a poor one. A good product is like a wise guide that enables customers’ transformation.

Customer transformation should be at the heart of a great product narrative, not manipulation, because transformation is valued higher than instant gratification. For example, social media platforms hijack our need for belonging and significance, creating narratives where we’re constantly performing for validation. Manipulative narratives do thrive, but not for long.

The right hemisphere has a unique capacity to perceive inherent value and meaning. Iain McGilchrist refers to it as valueception. Philosopher Max Scheler originally introduced the concept in his ‘Hierarchy of Values’. He classifies values into a four-rank pyramid, from the lowest to the highest. At the lowest, he places pleasure values, then vital values, and finally spiritual values, such as truth, goodness, and beauty. At the top, he places the sacred values.

Scheler argued that the depth and quality of the satisfaction we feel is directly tied to the rank of the value it corresponds to. Therefore, products that embody higher-order values such as integrity, honesty, truth, and beauty, in contrast with mere utility value, offer sustained and deeper satisfaction.

For example, Nonna’s kitchen, which fostered genuine community (spiritual value), is highly valued over Optimalbite, which cared for convenience (pleasure value).

A transformative story sets the character on a journey to the sacred, whereas a manipulative story takes the character in the opposite direction.

“When a person can’t find a deep sense of meaning, they distract themselves with pleasure” — Viktor Frankl.

This may sound great now, but does it hold in an Agentic future?

Narrative products in Agentic future

In a speculative future where we set goals for AI systems to make decisions and act on our behalf, this suggests that customers may not interact with brands directly in that digital space.

In the Agentic AI paradigm, if customers interact only with AI agents, which in turn interact with multiple brands and systems based on the criteria that are configured, then it appears that brand narratives may lose their power and break the mimetic desire loop, as most products become mere commodities for a narrative agnostic agent.

If the future unfolds in this way, brand narratives will become even more crucial for products to make sense to customers, or face the fate of extinction in the algorithmic optimisation. Narrative dead products or services will become commodities or mere tasks in a curated algorithmic world.

However, we humans do not always seek optimal solutions in everything; everyone wants a narrative to live for.

When agents will have to become the narrative mediators, brands will have to create their narrative agents, and digital products need to become agentic.

Regardless, physical, embodied experiences will remain crucial because certain narrative elements resist digital mediation — such as community rituals and sensory experiences. Brands need to foster real-world community experiences to strengthen the narrative to meet our deeper need for belonging.

On the negative side, as social media intensified narratives and their memetic processes exponentially, in the marketplace of Agentic AI, people can be trapped in a narrative echo chamber curated by AI agents. Even worse, governments or institutions can enforce their agents for compliance or control, and kill other narratives. This can be catastrophic for human flourishing. Therefore, it is important to protect ourselves with authentic and transformative narratives that inspire us.

Designing narrative-driven products and their agents is an emerging area to watch for.