When design stops asking why and starts asking, “Can AI do it?”

This advice is why designers are quietly losing strategic influence. We optimized AI interfaces for confidence. Organizations learned that confidence replaces judgment.

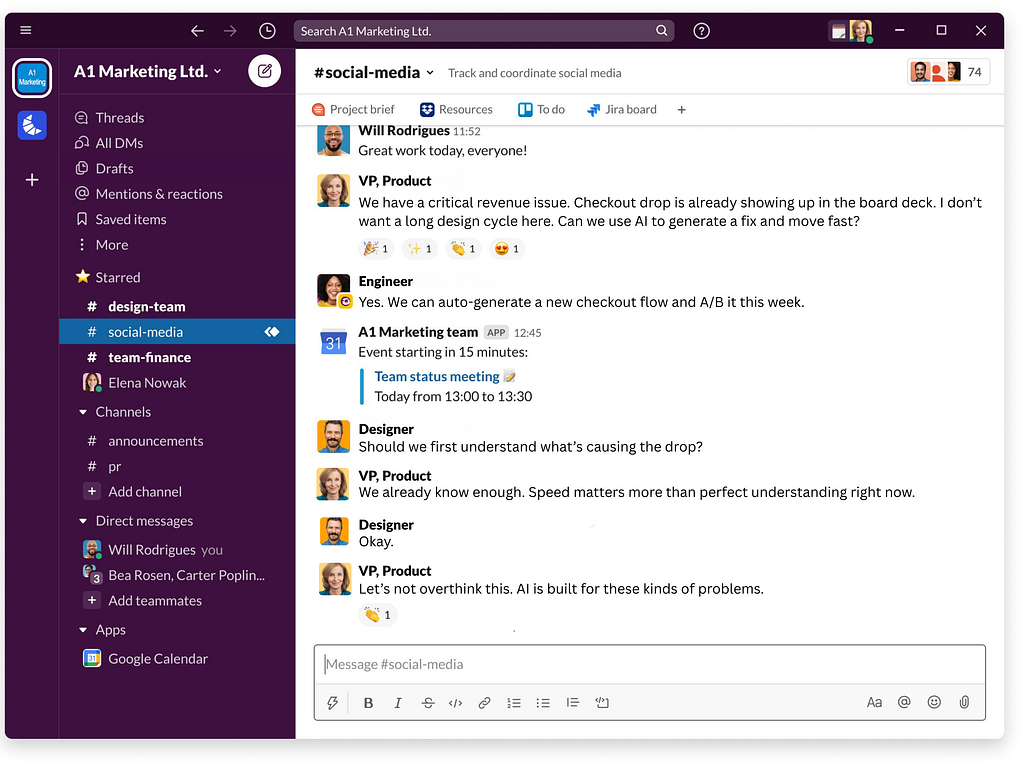

The question dropped into the Slack channel before the user research summary. Before the problem was clearly defined. Before anyone asked if users actually needed this feature.

Your product manager already generated three interface options in ChatGPT. Now they’re asking which one to build. Not whether to build. Not why to build. Which.

And when you slow the conversation down to ask those questions, you’re about to discover that strategic thinking now reads as bottleneck behavior.

This isn’t an accident. We designed the system that taught teams to trust AI outputs over design judgment.

Figma’s 2025 AI Report surveyed 2,500 designers and developers and found that 78% agree AI significantly enhances work efficiency. Only 32% say they can actually rely on the output.

That gap isn’t a quality problem. It’s a power shift.

22% designers now use AI to create first drafts of interfaces. 33% use it to generate design assets. The time from concept to visible prototype collapsed from days to minutes.

But something shifted that nobody warned you about: “Can AI do this?” started showing up at the beginning of product discussions. Not after user needs are validated. Not after strategic intent is clarified. It arrives first.

And when you slow teams down to ask strategic questions, you’re increasingly seen as friction rather than guidance.

We built this pattern. Now it’s being used against us.

We taught teams that polish means correctness

For years, UX designers optimized AI interfaces to hide uncertainty. Chatbots that sounded certain even when guessing. Loading states that implied thoughtfulness without revealing computational doubt. Systems that presented single recommendations with high visual confidence rather than surfacing alternatives with calibrated uncertainty.

We did this because research told us users trust confident systems. Smooth experiences read as competent. Hesitation feels like failure. As Erika Hall noted in her conversation with John Maeda, “the level of visual polish can lead designers and decision-makers to think that the concepts underneath are stronger than they are.”

The concepts underneath are what matter. But we wrapped them in interfaces that signaled completion rather than exploration.

Those design decisions didn’t stay contained. They taught organizations how to relate to AI outputs: polish became synonymous with correctness. Generation became synonymous with judgment. “AI created this” became implicit validation rather than a signal requiring verification.

We optimized for adoption. We got replacement.

The data exposes the disconnect

Figma’s survey of 2,500 designers and developers reveals the mechanic driving design’s strategic erosion:

- 78% agree AI significantly enhances work efficiency

- Only 32% say they can rely on AI output

- 68% of developers report AI improves their work quality

- Only 40% of designers say the same

The gap isn’t about AI capability. It’s about what organizations value. When engineers can generate functional code, they’re delivering tangible output. When designers generate questions about whether this serves users, they’re delivering… friction.

Julie Zhuo observed: “AI is redefining how we prototype. What once took days can now be done in hours, allowing designers to iterate and test more rapidly.” True. But iteration without interrogation isn’t strategic design — it’s production at scale.

Herbert Simon’s research on bounded rationality explains why this matters: under time pressure and cognitive constraints, people accept solutions that appear “good enough” rather than optimal. AI doesn’t create this behavior — it accelerates it by making “good enough” arrive so quickly that deeper evaluation feels wasteful.

When creation is cheap, teams learn to mistake speed for strategy.

What actually changed: Decision order flipped

Product teams used to follow a sequence: understand user problems → clarify strategic intent → explore solutions → generate artifacts. This ordering wasn’t arbitrary — it created space for judgment.

AI disrupted that sequence not by replacing designers but by making execution nearly instantaneous. When something can be generated in seconds, the act of creation no longer signals commitment. It signals possibility.

But teams don’t always treat it that way.

Once a generated interface exists — even provisionally — it reshapes the conversation. The artifact becomes gravitational. Feedback clusters around it. Critique becomes incremental. The deeper question (why this at all) arrives late, if it arrives at all.

John Maeda’s 2024 Design in Tech Report distinguishes between “makers” (designers and developers who create) and “talkers” (product managers who drive revenue). AI made it easier for makers to make. But it made it better for talkers to talk — because AI outputs give them tangible artifacts to discuss without waiting for design judgment.

When stakeholders see “working” prototypes in first meetings, the implicit question becomes: What do we need designers for?

The answer used to be: Strategic thinking. User advocacy. The discipline to ask why before how.

But when generation speed becomes the primary value signal, those skills read as obstruction.

The confidence problem we created

Most AI design tools are optimized for decisiveness. They generate singular recommendations with confident presentation. This makes sense from a UX perspective — confidence reads as competence, smoothness reads as quality. As design best practices emphasize, AI interfaces should “set honest expectations” and “show confidence.”

But between honest expectations and confident presentation, most products chose confidence.

This creates cascading problems. When AI presents one interface design with high visual polish, teams treat it as the answer rather than an exploration. Alternative approaches aren’t surfaced. Edge cases aren’t flagged. Uncertainty is smoothed over.

Research on automation bias has demonstrated this dynamic for decades: people are significantly more likely to accept system output even when it conflicts with their own judgment, particularly when that output is presented confidently. The effect strengthens as systems appear more capable and authoritative.

Human-centered AI research has long advocated that systems should “support human judgment rather than replace it” — surfacing uncertainty, presenting multiple options, enabling override. But velocity pressures push teams toward tools that minimize friction, not maximize judgment.

We designed the experience that trained organizations to trust confident outputs over strategic questioning.

What stopped getting asked

As generation becomes easier, certain questions surface less often in product discussions:

Why this approach instead of alternatives? When AI produces one polished solution quickly, exploring other directions feels wasteful. The existence of a “working” prototype creates psychological commitment before strategic evaluation happens.

What assumptions are embedded in this output? AI training data encodes countless decisions about what “good design” looks like, what user problems matter, what solutions are appropriate. These assumptions remain invisible unless teams actively interrogate them.

Who does this work well for — and who does it exclude? Rapid generation optimizes for median cases in training data. Edge cases, accessibility considerations, users who don’t match demographic norms get systematically overlooked.

As Mike Monteiro and Erika Hall have argued for years, design’s ethical responsibility is interrogating these questions before building. But when “Can AI do this?” shows up first, those questions get framed as barriers to velocity rather than essential judgment.

The strategic ground designers are losing

1 in 3 Figma users shipped an AI-powered product in 2025 — a 50% increase from 2024. Only 9% cited revenue growth as the primary goal. Instead, 35% said ‘experiment with AI’ and 41% said ‘enhance customer experience’ — goals that struggle to define measurable success.

Translation: teams are building because they can, not because they’ve clarified what problem requires solving.

This isn’t speculation. Nielsen Norman Group’s State of UX in 2026 names the existential tension directly: “Available roles will increasingly demand breadth and judgment, not just artifacts… The practitioners who thrive will be adaptable generalists who treat UX as strategic problem solving, rather than focusing on producing deliverables.”

But when artifacts arrive instantly via AI, organizations don’t value judgment that questions whether those artifacts should exist. They value judgment that makes those artifacts ship faster.

Jared Spool notes: “AI gives us an unprecedented ability to anticipate user needs. The challenge is balancing automation with human empathy in design.” The challenge isn’t technical. It’s organizational. When teams measure progress in shipped features rather than solved problems, empathy reads as slowdown.

68% of developers say AI improves work quality. Only 40% of designers agree. The gap reveals who’s winning the value argument. Engineers deliver code. Designers deliver questions. In velocity-obsessed cultures, questions don’t ship.

What separates successful teams from everyone else

Figma’s data on successful versus unsuccessful AI product teams reveals the pattern: 60% of successful teams explored multiple design or technical approaches, compared to only 39% of unsuccessful ones.

The differentiator wasn’t AI capability. It was judgment discipline.

Successful teams don’t slow down generation. They slow down after generation.

They treat AI output as a starting point requiring validation, not a conclusion requiring execution. They assume speed increases the risk of unexamined assumptions, not decreases it.

This aligns with principles Erika Hall has advocated for years: “80% of your job should be talking to people… The concepts underneath are the most important part.” But talking takes time. In cultures optimized for generation speed, time feels expensive.

Brad Frost’s work on design systems emphasizes that sustainable systems require “human relationships” and collaborative judgment, not just component libraries. But when AI can generate components in seconds, the relationship part gets skipped.

The uncomfortable truth about design’s complicity

Here’s what makes this particularly painful: UX designers built this problem.

We spent years optimizing AI interfaces for confident presentation over calibrated uncertainty. We designed chatbots to sound certain even when guessing. We created loading states that implied thoughtfulness without revealing doubt. We built systems that hid alternatives behind single recommendations.

We did this because users wanted smooth experiences. Because confident systems get adopted. Because our job was removing friction.

Those design decisions didn’t stay contained. They taught organizations that AI outputs deserve trust by default. That polish equals correctness. That questioning generated work slows teams down.

As John Maeda’s 2025 Design in Tech Report notes: “Computational thinking is invaluable… Work transformation is coming FAST.” We focused on making tools smooth. We didn’t prepare for how smooth tools would reshape what organizations value about designers.

What happens next

The real risk isn’t that AI will design for us. AI already designs with us, and that collaboration produces real value when guided by strategic judgment.

The risk is that organizations will stop rewarding the judgment part.

When “AI can do this faster” becomes sufficient reason to build something, design stops being about solving meaningful problems and becomes about demonstrating AI capability. User needs become secondary to technical possibility. Strategic clarity becomes friction to be eliminated.

As noted, teams cite ‘experiment with AI’ and ‘enhance customer experience’ as goals rather than measurable outcomes. They’re building because they can, iterating because it’s fast, shipping because velocity signals progress — all without the designers who used to ask whether any of this serves anyone beyond the team’s desire to ship AI features.

The choice that hasn’t disappeared yet

Design has always been about judgment. Not just making things usable or attractive, but deciding what deserves to exist in the first place.

AI changes how quickly we arrive at form. It doesn’t change the need for intent.

When creation is cheap, judgment becomes the most valuable part of the process. When generation is instant, the ability to say “this solves the wrong problem” becomes rare enough to be strategically important. When teams can build anything, knowing what not to build becomes the differentiator.

But Nielsen Norman Group is clear: “Adaptability, strategy, and discernment are the skills that will serve us best in the future… If you’re just slapping together components from a design system, you’re already replaceable by AI. What isn’t easy to automate? Curated taste, research-informed contextual understanding, critical thinking, and careful judgment.”

The question isn’t whether designers can prompt AI tools.

The question is whether organizations will still value designers who slow down to ask why — even when AI has already answered how.

When design stops asking why and starts asking “can AI do it?” was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.